From Book to Film: Part two

In the previous installment of From Book to Film, we discussed two films that, though adapted from a novella and a novel, respectfully, differed from their source material in terms of narrative structure, adding, expanding upon or even skipping over plot points while still managing to create a strong, everlasting cinematic experience.

On this edition, two more films will be discussed but both happen to be extremely faithful and representative of their individual adaptations. Both films created a world almost identical to the author’s vision and boasted critical as well as box office glory.

Both films are powerful, stimulating and beyond successful in their scope. As moviegoers and readers, we can only hope adaptations of this quality lead the way for more, high quality translations.

Sin City

Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez seem an unlikely creative duo, but in 2005 they teamed up and adapted one of Miller’s most creative series graphic novels to the big screen. “Sin City” is not a movie based on a comic, but rather a comic book movie in the purest and most dedicated form imaginable. Miller and Rodriguez literally took panels from the formers graphic novels and turned them into beautifully photographed, flickering images on the big screen, making the translation from novel to film seamless.

The story follows the inhabitants of the titular city as they make their way through Sin City’s corrupt and dangerous streets. The movie follows three of Miller’s novels, each a full story on their own, but when strung together on film, creates a wide spectrum detailing the livelihood of the cities righteous and unrighteous dwellers.

The first third of the film follows Marv, played magnificently by the brutish yet tender Mickey Rourke, who was genuinely snubbed for an Oscar nomination. After spending the night with a beautiful hooker, Goldie, the only woman that has treated him right, Marv wakes up to find her dead and the police already on their way. Fighting his way through hoards of police officers, Marv realizes he has been set up and goes on a violent rampage in an attempt to prove his innocence.

Rourke bleeding it up as Marv

Rourke is almost too perfect in the role of Marv, a man continuously beaten by life but who never learned to stay down. He is tough and brooding and wholly sympathetic, creating an anti-hero for a hero-less generation.

The second act of the film finds us switching gears to Dwight, an equally violent and unstable man who gets caught up in a situation that could threaten the long standing peace between the whores of Sin City and the police who let them go about their business as long as they get a cut of the profits.

Featuring the talents of Clive Owen, Benicio Del Toro, Rosario Dawson and Britany Murphy, this act is just as exciting as the first, shedding more light onto the layout and general disposition of a city fortified by the corrupt and held together by morally ambiguous characters, all of whom are just trying to get by.

The third and final chapter switches gears once again, this time to former police officer Hartigan, who was betrayed by the system supposedly sworn to protect the city but in fact just goes on to destroy it. After being locked away for almost ten years, Hartigan is released but is soon put right back into the action after a young girl is kidnapped by a notorious rapist.

Bruce Willis, Jessica Alba and the criminally underrated Nick Stahl fill out the cast for this final chapter and each one of them keeps up the dark, unrelentingly violent tone and bring to the table a sense of boiling noir.

Each of the three parts is highly representative of their source material. Rodriguez configured the storyboarded the movie based on Miller’s panels, and even the dialogue is almost identical from novel to film, creating a unified experience that is as much a joy to behold as it presumably was to create.

Rodriguez stuck to what Miller had created and in the process made “Sin City” the perfect adaptation.

No Country for Old Men

Cormac McCarthy never had much luck in seeing his work translated successfully to the screen. But in 2007, the Joel and Ethan Coen shared with audiences what an adaptation can do and how three artist’s minds could be so in tune with one another’s.

Little changed from McCarthy’s story of drugs, death and the commerce of life to the Coen’s big screen adaptation. The characters remain intact, the plot points fall as they should and the highly invocative world McCarthy enlightened his audience to is brought to life with a scintillating tact by the brothers Coen.

“No Country For Old Men”, both the book and the film, details the events of a drug deal gone sour and its unfortunate aftermaths. Llewelyn Moss, a Vietnam Vet who lives in a trailer park with his wife Carla Jean, stumbles upon the corpses of all those involved in a large scale heroin deal.

A natural hunter, Moss goes on to discover the last man standing, who holds in his dead hands more than $2 million in cash. Moss takes the money and runs, fleeing from the Mexican cartel, Sheriff Tom Bell who only wants to help Moss but has trouble understanding all the senseless violence that seems to be left in his wake, and the menacing mercenary Anton Chigurh.

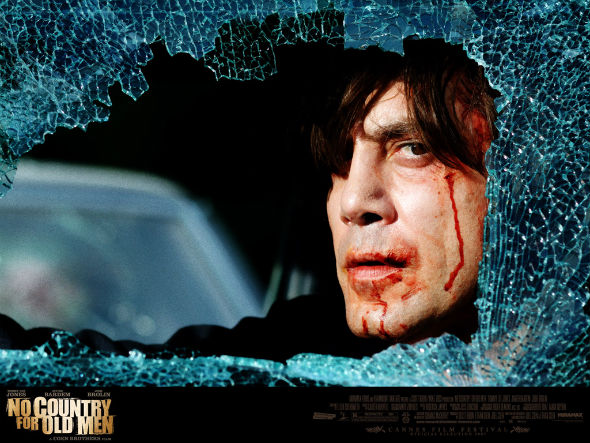

Broling as Llewelyn Moss

Nothing seems lost in the translation from novel to screen and the Coen Brothers must be commended for their astute and respectful adaptation on a novel that, in lesser hands, could have seen its themes and overall impact dwindled by less capable filmmakers.

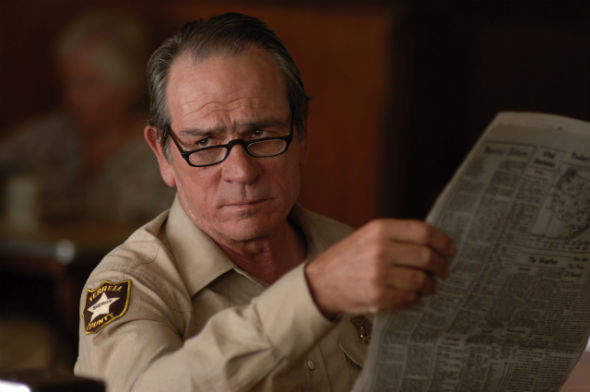

The Coens wrangled up a stellar cast in the process, giving Josh Brolin, Tommy Lee Jones and Javier Bardem the deepest, most intricate and defined roles of their careers, all of whom handle the task with more than their fare share of success.

Jones as Sheriff Ed Tom Bell

The only, major difference from the novel compared to the film, is a subplot involving Sheriff Bell and his guilt for leaving his company behind during World War II, a move that left him alive but all the members of his outfit dead. And while this could have easily been put in the film, the Coens, in their infinite wisdom, decided to do away with this subplot and have Bell see the actions unfolding before him as equally troubling as his past.

The film won four Oscars and once again proved that, if done respectfully and with appropriate gait, novels can be made into great films.