Books to Film: Part One

A novel is such a singular experience it is no wonder that adapting a book to the medium of film is as arduous a task as any. When you read, you are alone. Not in the sense that no one else is around you, but rather that you are the reader and the narrator and the painter of the scenes in your head. You provide the voices and translate the imagery to fit the way you perceive the story.

Film, on the other hand, is a collective work. Literally hundreds of people work on any given film and the images that are conjured are from the perspective of many different people, not just one.

So when a director decides to adapt a book or short story, they must make the translation so powerful and evocative as to sway the viewer from the images they have created in their own mind, and believe earnestly that the translation on screen is just as worthy as the source material.

There have been hundreds of films adapted from books, most of which fall flat when compared to the original, published works. But every so often there is a film that has been adapted from a book that shines a new light on the art of adaptation.

So without further ado, here are is Part One of this series, highlighting great films that were adapted from novels, short stories or other published works and created an experience akin to and as equally enthralling as the source material.

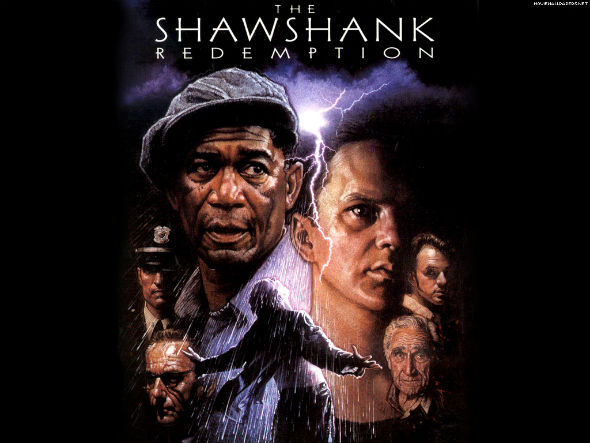

The Shawshank Redemption

Stephen King is perhaps the most adapted author of all time. From horror novels, to short stories, Hollywood seems infinitely dedicated to providing King’s works with a cinematic counter part. And while most of his horror works, of which he is most recognized for, have fallen flat when translated to the big screen, it seems his novellas have been adapted with the most success and with an unflinchingly high quality.

From “Stand by Me” to “The Green Mile”, his novellas have provided an outlet for a different voice from one of the world’s most famous author’s. It is a voice that does not have to rely on super natural horror, but rather the real horror of mankind, the type that stirs the soul and brings into question the decency of the human race.

And never has his work been translated with more tact and attention to detail than in 1994’s “The Shawshank Redemption”. Based on his novella Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, the film follows newly convicted Andy Dufresne, played meekly yet intelligently by Tim Robbins, as he tries to cope with a life-long sentence in jail for a crime he claims not to have committed.

While on the inside, he befriends Red, played by the majestic Morgan Freeman. Red is a man who is known to “locate certain items from time to time” and it is through his eyes and heavenly narration that we see Andy and the rest of the inmates in Shawshank prison.

Written for the screen and directed by Frank Darabont, “Shawshank” is a film that delves deep into the nature of man and criminality, as well as the loss of humanity when kept confined in a world that revels in and functions on the misdeeds of society.

Darabont has taken King’s work, which was very good by its own merits, and given it an injection of life, soul and unnerving humanity that allows the film to progress fluidly on the screen, never once letting go or allowing the audience to escape its moving and thought provoking illustration of a prison so corrupt that the inmates become the heroes.

It is a classic film that only grows more impressive with age and more insightful with each subsequent viewing. It is a perfect adaptation that relies on the source material for inspiration but makes its way uniquely and with a new, wholly cinematic voice.

Here is a scene from the movie in which, after six years of trying to allocate funds for a library, Andy receives a check from the state as well as a large collection of used books and records to get his project started. It is a moment of joy for the imprisoned man, who decides to share the wealth with his fellow inmates, no matter the cost.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y_lp4_Jfz7U

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Author Ken Kesey was not very happy with the film adaptation of his 1962 novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”. In Kesey’s original text, which is as expertly executed a novel as one can find, the story is told and unfolded from the perspective of Chief Broomden, the large Native American man who has spent years in the mental institution in which the story takes place, convincing the staff and hoards of doctors he is mute. Broomden’s voice is unique and inspired, offering a beaten yet enlightening perspective on a demeaning world that forces a strong, well-meaning man to silence.

Broomden holding tight to McMurphy

So in 1975, when the film adaptation of Kesey’s work began, it was, of course, a travesty in his eyes to have the point of view switched from his quietly graceful Broomden to the brash, never folding Randall P. McMurphy, an equally powerful and provocative character but one whose perspective is entirely different from that of Broomden’s.

And while the book and the film are decidedly different from one another, maybe more so than any other successful adaptation, the film still provides the heavy sock to the stomach and soul displayed in Kesey’s original works.

The film follows the day-to-day lives of the inmates at an Oregon mental institution, whose spirits are continuously squandered by the conniving and treacherous Nurse Ratched. Ratched has a firm, autocratic rule over her ward and she takes pride in the sternness of her gait and the profound impact of her ruling fist.

So when her ward is invaded and her strength put into question by the free spirited and untamable R.P. McMurphy, the two are immediately put at odds for control of the ward and the freedom of the inmate’s spirits.

Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched

Milos Foreman did a fantastic job at creating a sense of time and place. The hospital is a character in and of itself, and the fact that they filmed on location at a real mental institution only adds to the sense of pained reality. McMurphy is played to the utmost perfection by Jack Nicholson who plays the perfect foil to the uptight Nurse Ratched, played harshly yet sympathetically by Louise Fletcher.

The two are, in essence, opposites and McMurphy’s struggles to be free are continuously undermined by Ratched, who wants nothing more than to keep her patients under control and under heavy medication. The plot is essentially the same between novel and film, though in the novel there are more revelations to the characters and more background to their situations, and the script does a fine job at translating the book to fit the medium of film. There is more humor in the film than the novel, but the heart is still there as is the endless battle between personal freedom and overbearing rule.

Though Kesey had his issues, since the book is decidedly different form the film, Foreman has created a world where the characters are so well defined and their motivations so clear that is hard not to appreciate this unique but equally powerful translation.

In this scene, McMurphy has just lost a battle with Nurse Ratched but decides to keep fighting the war. Using his imagination, he sparks life into the other inmates, which is exactly what the nurse has been fighting against.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfFJLFeyI1o